As most of you saw in September, I (Justin) summited the highest freestanding mountain in the world: Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania Africa at 5895 meters, or 19,341 feet.

Patrice previously blogged about the origin story and training, but the recap is that my high school buddy, Luke, called me up and asked if I would like to climb Kili. Before he could finish his sentence, I was already committed. Then he told me the caveat…We would be taking a man confined to a wheelchair to the top. I said even better.

That started my journey with the nonprofit, My Impossible, and the inspirational leader Jeff Harmon. I again would like to thank family and friends who donated to this non-profit to help make this “Impossible become a Possible”. It meant the world to me and the team to see such support to this cause.

I joined the training trips in Charlotte and Colorado Springs where the team participated in a Spartan Race and did training hikes. The goal was to get to know each other and bond, as well as learn how to manage a wheelchair while climbing a mountain. The team itself consisted of 30 members from all over the states, but most of the team was from the New Jersey area where Jeff lives. It was a great mix of ages—from 16 to 60 years.

After a long summer of guiding and public speaking, I left at 2am on Thurs, September 4th for the big trip. My first observation was that it took an incredibly long time to fly to Africa! Anytime we leave the state, the first leg is always the 3.5-hour Fairbanks to Seattle, so that was no different. Then I had an usually long layover in Seattle. Next, I boarded Qatar airline for the 16-hour flight to Doha Qatar. That was another long layover, but my “status” got me into a beautiful lounge where I ate, drank and even took a shower! The last flight was about 6 hours to the Kilimanjaro airport, arriving Saturday morning 9/6 at 7:30am. (Spoiler alert: the return flight was even longer!).

After dropping my bags at the hotel, I joined about 10 teammates for an all-day tour of the village of Moshi. We visited the local farmers market, then a long hike in the woods outside of the village where we saw monkeys and no other people. Then for lunch and shopping. When we returned to the hotel around 6pm, I crashed hard and slept until the next morning.

The next day, most of the team had arrived and about 20 of us set off another tour. This time we traveled about 2 hours on a dusty dirt road to a native African village where the tribe welcomed us with open arms and we dressed up and participated in some traditional ceremonies. Then to a hot spring pools where the we swam and swung from trees and dropped in to the pools and ate a hot lunch. We arrived back at the hotel and had team dinner and meeting with the guiding service and finished up packing.

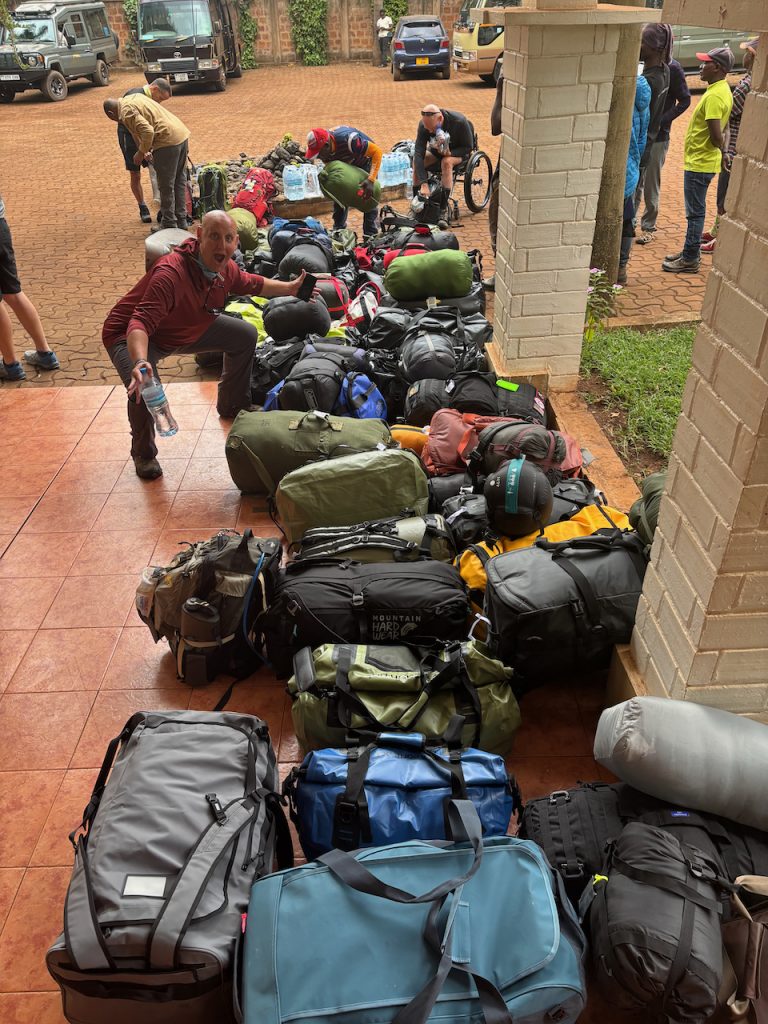

Mount Kilimanjaro is a unique mountain because the government requires climbers (even if you are African) to hire guides and porters (locals who carry equipment & cook food). There are several routes to the top and the Marangu route allowed us to stay in sleeping huts opposed to camping. It made it easier for the group as well as for the wheelchair. Our bag limit was 33 pounds—which the porters carried—and we simply carry a day pack for what we need during the day. Most guided groups consist of 2-20 climbers, but of course our team was atypical with 30 people. This meant we had well over 70 support staff, which included hiking guides and porters. I should mention, the intention was never for the guides/porters to maneuver the wheelchair up the mountain; that duty was meant to stay on us. Anyway, to say our team was a small army was an understatement. We had well over 100 people involved in this mission! Besides our 33-pound duffels, the porters carried cooking supplies and even toilets. Yes, if you wanted to, you could hire a single person to carry a personal toilet for you to use as you were hiking, and set it up outside your sleeping hut for convenient use. You all know me and know that nature is my bathroom, so I chose to use the pit toilets at camp and found wonderful spots to dig a hole.

After a nice breakfast, the small army loaded up three vans for the 1.5 hour drive to base of the mountain. We all had to register for the climb at the ranger station, then had a team prayer and finally started the actual climb after 12pm. We had a 5-mile climb from Marangu Gate to Mandara Camp, from 6,046ft to 8,858ft. Day 1 terrain was full of large trees and plants lining the sides of the trail with monkeys swinging overhead calling to each other. Even though it was a beautiful hike through the rainforest, it was already hard. There were 3 teams of about 10 people to work in shifts to assist with the wheelchair. While on the chair, you might be attached to it either via a harness system or simply just holding on to provide support. Each shift would be anywhere from 20-45 minutes, depending on the terrain. The last 3 miles of Day 1 included lots of lifting and pulling the wheelchair. It was a constant obstacle course of navigating car size boulders, uneven sloping trail, bridges, creeks, trees and plant life and narrow passages, and we still had several days of this to come. We made into camp around 7pm, so about 7 hours on the trail. We all expected it would take us a bit longer than a normal expedition, but nearly every distance was doubled in time. The huts ranged from 4-10 people per room, and I was assigned to a 4-person hut. The crew had dinner set up within an hour of arrival, and we ate potatoes, veggies, sauerkraut and some type of fish. With my stomach issues, I was very careful on what I ate and drank and would be very picky on food choices.

Day 2 was a 7-mile climb from Mandara Camp at 8,858 feet to Horombo Camp at 12,205ft. We were up at 6am, but did not leave until after 8am. I was concerned about our departure times, since my previous climbing experiences taught me to leave before sunrise to beat any heat of the day and avoid climbing at night. However, the guiding company didn’t seem concerned. This proved to be the hardest day for all of us. Some people could not help out on the chair anymore because of exhaustion, especially given the fact we were gaining elevation and altitude was starting to mess with people. Our teams of 3 merged into whoever could help, just speak up and hop on chair duty. I was worried not only for Jeff, but for all those near the wheelchair in the case they could get caught under it—even snapping an ankle—or knocking someone down. For me personally, I felt like I was on chair duty much more than I expected, and I pushed myself to my exhaustion limit. Another side note, there were definitely too many cooks in the kitchen, as you could expect in a large group. Lots of opinions on how to correctly maneuver the wheelchair, etc. Around 5pm, we decided to send half of our group—those who were most exhausted and could not help out anymore—ahead to the hut. We also decided we needed help with the wheelchair from the guiding company. Again, this was never the intention. But it was clear we needed it, and I was glad our leaders realized help was necessary. The porters jumped right on the chair and worked their asses off the rest of the day. They spoke Swahili to each other, and moved so efficiently though the terrain that they were so familiar with. It ended up being a 12-hour day, and we were all exhausted and spent. We had a strange meal of rice and some type of meat and everyone crashed hard. This evening we had a bunkroom above the dining room that slept 20 of us.

As expected in a 20-person bunk room, it was a rough night of sleep, with maybe 3 hours of actual rest. We left at 8am from Horombo Camp, and had a 6-mile trek to Kibo Camp at 15,430ft. The trail was wide for easy chair maneuvering, and even had lots of flat sections. Being out of the rainforest meant we were above the clouds and exposed, but the weather was great. We continued to work with the porters for help with the chair—mixing team members in with porters. It was very efficient and we made great time. We even beat the lunch porter team to the lunch spot by 20 minutes! We rolled into Kibo Camp at 2:30pm. Even though it was an “early” and “easier” day, I could see the exhaustion splayed across many team members’ faces. At 15,430 feet, this was the highest any had been, and altitude is no joke. We all settled in for some rest after a spaghetti dinner.

Day 4 was summit day, of course the hardest day. It would be 8-miles roundtrip, 4 miles with 4,ooo feet of elevation gain from Kibo Camp to Uhuru Peak (19,341 ft), then 4 miles back down to Kibo Camp 15,430ft. I immediately had a few concerns. Our wakeup call was at 3am, then we started the climb “late” (in my opinion) at 5am. I was very surprised the African guides did not conduct a safety meeting, didn’t talk about turnaround times when to stop the climb to avoid dangerous situations like climbing down in the dark, and what the signs of altitude sickness were. The guides also never taught the group about how to climb at altitude. Jeff did make it a point to say that if he could not summit he wanted as many of us that could to make the attempt. I had brought this up a few times during our monthly Zoom meetings. As the only person who had been on long climbing and hiking expeditions, I stressed that it would extremely unlikely that we would all make the summit, and even more unlikely that we would all reach it together. I believe most of our group assumed this would be a walk in the woods, and it would be one happy group at the summit for a massive group picture. So when we departed at 5am for summit day without real-time expectations discussed, about half the group members left and sort of did their own thing to get to the summit. I strapped into the chair for shift 1—again with the mixed help of the porters and team members. There was no real trail but a path in the dusty scree field that zig zagged up the mountain. We were moving slower than a snail, and pure exhaustion was rampant. The wheelchair was also breaking down—the two front tires shredded off, and we could only rely on the back tires. I switched on and off the chair for hours, sometimes on for mere minutes, other times trying to push the 20-30 minute mark. We watched the sunrise over the clouds and the smaller peaks below.

Around 18,000 feet, I could tell there was a second group of people itching to break off from the wheelchair group to get to the summit. I know my abilities really well, and knew I could personally get to the summit, but doubted at this point that Jeff and those staying behind with the wheelchair could get to the summit—mainly because of the snail’s pace and fact that it is generally unsafe to climb in the dark under any circumstances. In any case, I talked with Jeff and we agreed it would be best if I went ahead a bit and helped the group in front. We had an African guide with us, but he was not practicing the “rest step,” which is an energy-efficient technique for climbing at altitude. The group seemed happy for my “rest step” guidance, and we slogged up the mountain. Our African guide was ahead of us to show us the “path” up. We actually witnessed numerous other expedition guides running down the mountain with clients in states of severe altitude sickness trying to get them to lower elevations. It was at this point that I realized the goal of this company—as well as maybe most companies—was to summit. This was pretty scary to see, and I hoped no one in our group would have any serious altitude sickness.

There are several “false” summits along the way, and they are great turnaround options for those who may not get all the way to the top. We reached one of those—Gillman’s Point at 18,885 feet—which looks down into the volcanic crater. You could see the true summit of Uhuru Peak (19,341 ft) from there, but it is always further than it seems. For me and my small group of team members, it was 2pm at Gillman’s Point, and getting close to my personal turnaround time. If we continued to the summit, we would be hiking down in the dark. Two people made the decision to turn around here. However, the rest of the group was in good spirits, and I could tell they still had the energy. As long as we walked like slow astronauts and breathed properly, I knew I could lead this team safely to the top. A group of 9 of us reached the summit around 4pm! We spent 20 minutes taking pictures, then headed back down.

I was still concerned about the judgement calls of the guides, as I could see that Jeff and the wheelchair team were still making their way up. We ran into that group just above Gillman’s Point and were shocked to hear that they were still going for the summit. Another teammate and I talked to the owner of the company and inquired why they were not turning back. He was adamant that the top was the goal, and they could get everyone there. I expressed my concern to several team members about their safety. It would be pitch black for them, plus getting colder. My mountaineering motto is always “getting to the top is optional, but getting down is mandatory.” They didn’t seem to share my concern, and they definitely were relying on the guides for advice, so I had to leave it. My team layered up, put on headlamps and hiked back down to the hut in darkness. We were all exhausted—physically and mentally. The climb down any mountain is always the hardest for me. The elation of the summit wears off, and you can easily let your guard down, dragging your feet and letting your mind wander. We reached the hut around 9pm, making it a 16 hour day.

We looked up and saw other headlights up there, knowing it was Jeff’s team. I didn’t learn until the next morning that Jeff and the rest of the team decided to turn around short of the summit. Jeff said it best: it was never about the sign at the summit, it was about bringing a group of people together to see what was possible. In the end, the entire team made it back to Kibo hut in one piece. I did learn that many people from our team were throwing up with altitude sickness on the mountain, and were not turned around by the guides even in that state. I had several team members approach me and thank me for my leadership, advice and guidance, and that meant a lot to me. I like to think I am a safe and experienced climber, and I honestly felt like I had more experience in terms of mountain safety—at least by US standards—than our guides. Like I said, I am just so grateful everyone made it down safely and my worst fears were not realized.

When Day 5 dawned, pretty much everyone was destroyed, but we headed all down the mountain to Mandara Camp to 8,858ft. And the mood was a tad somber because some people were riding high from their summit accomplishment, others were pissed they didn’t make it, and others were just recovering from altitude sickness. In retrospect, I understand everyone’s mixed feelings. There is the physical distress of such a brutal climb and the allure of “being so close to the summit,” which is why a climb is as mental as it is physical. Again, this was the first time most of these people were on a climbing expedition, and expectations were not as clear as they could have been.

Getting to the base of the mountain, we all celebrated this incredible feat. Jeff made his impossible possible, defied the odds and showed the world that you can do anything you put your mind to it. I’m so proud for everyone that stepped out of their comfort zone and embarked on this journey—most people said this was the hardest thing they ever done in their life. I made some lasting bonds with teammates. This was my first time in a 3rd world country, which was moving in itself, and I learned so much about the African culture. I’m also so proud of myself—I haven’t climbed any mountains since some of my surgeries, and I was happy I felt so strong and was able to help make this a successful trip.

With that I leave you for now…until my next crazy adventure.

(Thank you to several teammates who contributed many of these photos!)

Discover more from Wandering La Vignes

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Well done Justin! I’m so proud of you!Love, Dad

What a trip. Having you there with your experience and knowledge was a comfort for sure!

Awesome recap! I love all the pictures. I’m so proud of you. What a major accomplishment.

Awesome adventure. You are amazing.